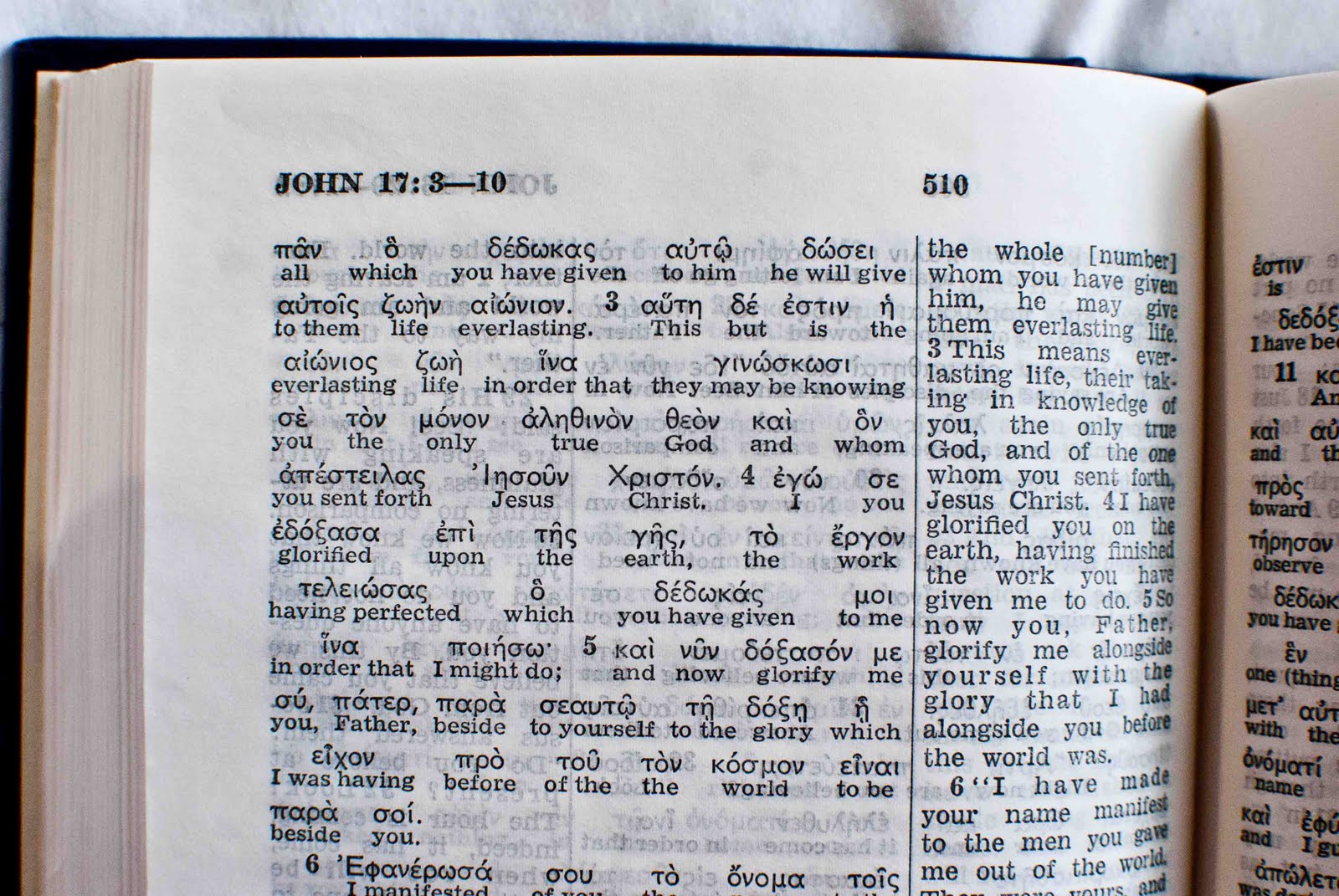

John 17:5: A Verse to Be Trapped By

November 1, 2016

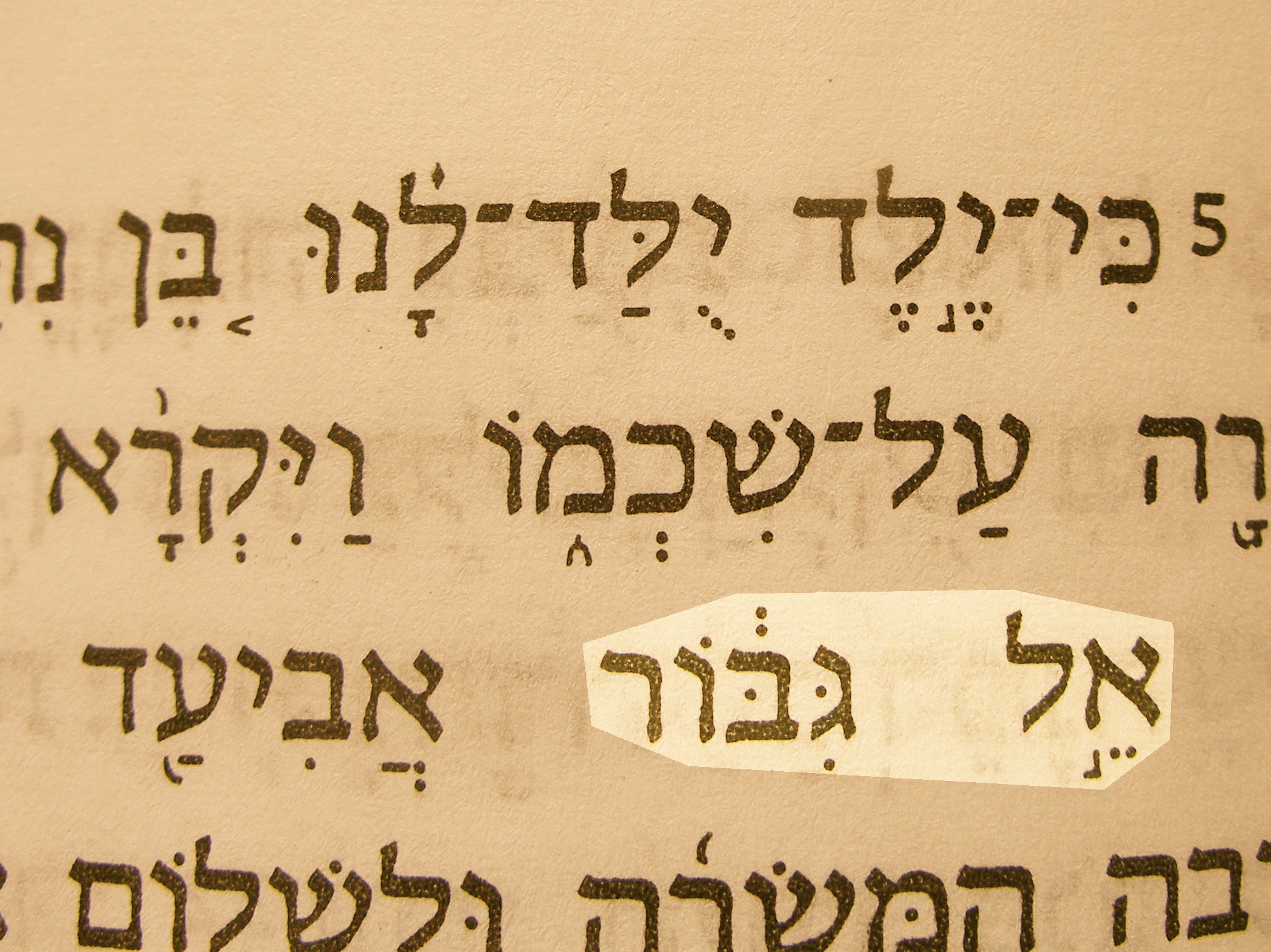

Is Jesus “the Mighty God”? A closer look at el gibbor in Isaiah 9.6

November 1, 2016Colossians 1.15-17 Explained

From, Christology in the Making by James Dunn.

[For modern interpreters the phrase ‘The firstborn of all creation’ v.15b, denotes] precedence in rank rather than priority in time, first over creation rather than first created being. If this is the correct interpretation then perhaps once again the thought is primarily of the exalted Christ – ‘he, through whom God already recognizable also in his creation becomes understandable’. Yet, since the dependence on the wisdom tradition is again so strong here, we should recall that we have there a similar ambivalence in the talk of Wisdom, with Wisdom spoken of both as created by God (Prov. 8.22; Sir. 1.4; 24.9) and as the agency through which God created [Prov. 3.19; Wisd. 8.4-6; Philo, Det. 54; Philo speaks of the Logos as protolonos (Agr.51; Conf. 146; Som. I. 215]. In which case we may well have to think ourselves back into the context of thought prior to the Arian controversies and accept that the hymn’s and Paul’s understanding at this point shared something of that ambivalence. The important thing about personified wisdom was that it was a way of speaking of God’s creative activity, of God’s creative acts from the beginning of creation. Whether this means that God’s creative power is prior to creation or can be spoken of as the beginning of creation becomes a question only when personified wisdom is understood as a personal being in some real sense independent of God. It is more than a little doubtful whether this question had ever occurred to Paul or to the hymn writer, presumably because their thought of personified wisdom was wholly Jewish in character and the language only became personalized for them when it was the exalted Christ who was in view.

[‘For in him were created all things…’ v.16a] Paul intends the fuller meaning: in him in intention, as the one predetermined by God to be the fullest expression of his wise ordering of the world and its history. This is certainly the way in which the writer to the Hebrews treats the aorist tenses in Ps. 8.5f.: that which the Psalmist referred to the creation of man, Hebrews refers to Christ, since only in Christ is the divine intention for man fulfilled [Heb. 2.6-9]. So possibly also with Col. 1.16: that which Jewish thought referred to divine wisdom in creation, the Colossian hymn refers to Christ, since only in Christ is the divine intention for creation fulfilled. Yet while this thought is certainly present (‘all things were created…to him’—eis auton), the hymn also says ‘all things were created through him’ (di autou—both dia and eis—v. 16e).

We must rather orient our exegesis of v. 16a more closely round the recognition that once again we are back with wisdom terminology—as perhaps Ps. 104.24 (103.24 LXX) makes most clear.

[The parallel line in the original hymn (v. 16e) and the parallel with Ps. 104.24…lead me to understand the en in an instrumental rather than local sense (see particularly Lohse, Kolosser, p. 90 n. 4—ET, p. 50, n. 129). But even if we understood en in a local sense (see particularly Schweizer, Kolosser, pp. 60f.) we are still in the realm of Hellenistic-Jewish thought concerning divine Wisdom and the divine Logos, since it is precisely part of the ambivalence of the Logos in Philo that it is both instrument (e.g. Leg. All. 111.95f.) and ‘place’ of God’s creative activity (Opif. 20). See also A. Feuillet, ‘La Creation de l’Univers “dans le Christ” d’apres l’Epitre aux Colossiens (1.16a)’, NTS 12, 1965-66, pp, 1-9; also Sagesse, pp. 202-10. There is no need to hypothesize a pre-Christian Primal Man myth to explain the language here (against F. B. Craddock, ‘”All Things in Him”: A Critical Note on Col. 1.15-20’, NTS 12, 1965456, pp. 78-80; and the broader thesis of H. M. Schenke, ‘Der Widerstreit gnostischerund kirchlicher Christologie im Spiegel des Kolosserbrlefes’, ZTK 61, 1964, pp. 391-403, that in Col. one gnostic christology opposes another).]

This may simply be the writer’s way of saying that Christ now reveals the character of the power behind the world. The Christian thought certainly moves out from the recognition that God’s power was most fully and finally (eschatologically) revealed in Christ, particularly in his resurrection. But that power is the same power which God exercised in creating all things – the Christian would certainly not want to deny that. Thus the thought would be that Christ defines what is the wisdom, the creative power of God he is the fullest and clearest expression of God’s wisdom (we could almost say its archetype). If then Christ is what God’s power/wisdom came to be recognized as, of Christ it can be said what was said first of wisdom – that ‘in him (the divine wisdom now embodied in Christ) were created all things’. In other words the language may be used here to indicate the continuity between God’s creative power and Christ without the implication being intended that Christ himself was active in creation.

[‘He is before all things…’ v.17] we do not have a statement of Christ as pre-existent so much as a statement about the wisdom of God now defined by Christ, now wholly equated with Christ.